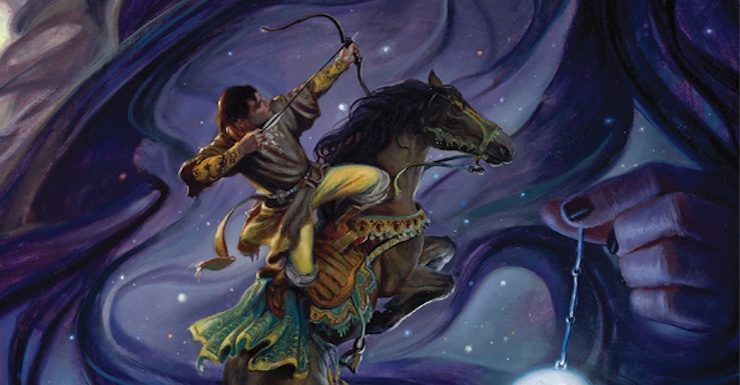

Elizabeth Bear’s novel, Range of Ghosts, begins the Eternal Sky trilogy, set in a world inspired by 12-13th century Central Asia (also featured in her 2010 novella Bone and Jewel Creatures). The book follows a set of exiles and outcasts from different kingdoms who come together as war and strife throw their previously settled societies into chaos. As civil war flames across the steppes, political intrigues unsettle royal dynasties elsewhere, and at the center of it all a murder-cult, an offshoot of the Uthman religion of the Scholar-God disavowed by its own society, sows discontent and infighting along the Celadon Highway with the intent to snap up all of the weakened kingdoms at the culmination of a great war.

Temur, a grandson of the Great Khagan, and Samarkar, once-princess of the Rasa dynasty and now a wizard, are the focal characters of the novel, which revolves around the developing political situation as much as it does their personal growth, relationships, and journeys. This is a complex fantasy, a tapestry woven of characters, intrigues, action, and epic—in the real sense of the word—conflicts that are only just beginning in Range of Ghosts. Those epic conflicts of religion and empire are reflected in the skies themselves; overhead, the heavenly bodies reflect the primacy of a ruler and a given faith. In the steppes, under the Qersnyk sky, there are moons for every one of the Great Khagan’s sons and grandsons. The skies of Rasan are different from the skies of the Rahazeen; what floats overhead—and what doesn’t—is immensely significant, and foregrounds the grand scale of the battles being waged.

However, despite that scale, the book never loses its grounding in interpersonal interactions and the significance of a single life, united with other single lives. This novel plays with the rules of high fantasy and epic fantasy, sidestepping many classic and contemporary tropes with ease while constructing a fabulous second-world populated with powerful women, moments of kindness and stillness amidst the horror of war, and the personal made intensely political. The vast is the personal, and the personal is the vast. This is not an easy balance to strike, but Bear manages it with a deft hand. The sense of kingdoms resting on the backs of people, and those people’s decisions having major consequences, is sometimes lost from these sorts of stories—or, worse, the story could revolve around a “singular hero,” where the significance given to one person alone is past the bounds of belief. Range of Ghosts manages to avoid both pitfalls and weave together a balanced, well-distributed narrative that is grounded in the personal, even the mundane, while it explores large-scale conflicts.

This grounding in the mundane and the humane, in the midst of great tragedy, death, and strife, is a delightful change from the “all gritty, all the time” channel of contemporary epics—and strikes me as more realistic, not less. Despite horror, these characters have moments of laughter, moments of passion, and moments of hope. They are more as a whole than the simple sum of their parts, and watching how Bear folds their lives together, into each other, and among each other through dialogue and seemingly-simple action is a pleasure. The world-building is positively breathtaking in its detail and its fantastical twists and turns; the magic systems, the religious systems, and the cultural heritages of the various peoples in the book are all richly portrayed—an obviously large amount of research has gone into this project. Worth mentioning on this note: while white people are mentioned offhand by Temur a few times in discussion of trade and travel, every character in this series so far is a person of color, excepting Hrahima. Considering that this is an analogue of 12-13th century Central Asia, that’s to be expected, but is still a refreshing change from the endless flow of European-based fantasy epics in which we might be lucky as readers to encounter, perhaps, one brown person in the course of an entire series. (I’m looking forward to reading Saladin Ahmed’s Throne of the Crescent Moon, which many reviewers have been mentioning in context of Range of Ghosts, for the same reason.)

There are other things that I found immensely pleasing about the novel, especially the sexual politics and the range of opportunities offered to women as characters who have, wield, and understand power. The range of women in the novel is a joy. Samarkar is the character who brings the novel to life for me; she is the once-princess who risks death to become a wizard “for the chance of strength. Real strength, her own. Not the mirror-caught power her father, his widow, her half-brothers, or her dead husband might have happened to shine her way.” (38) I was struck more, however, by the other Rasan princess they must rescue near the end of the novel: Payma, a fourteen-year-old pregnant woman, whisked away by Temur, Samarkar, and Hrahima to save her from being murdered for the fact that she carries the disgraced brother’s heir (and hence is a threat to the brother who has taken power).

At first, this seems like an unempowering scenario. She is, after all, being rescued. However, as their escape continues, she runs on her slippered feet until she tracks blood behind her with no complaint; she takes care of horses on the trail and rides with no complaint, she holds her own in an attempted assassination. Her power is a different kind of power from Samarkar’s, or Hrahima the tiger-woman’s, but it is still strength. I appreciate the nuanced women in this book—including Edene, the woman whom Temur would marry if he could have. [Editor’s note: the following is whited out for spoilers; highlight to read] Her captivity and her escape from the Rahazeen are nerve-wracking, especially as we-the-reader know that at the close of the novel she has fallen for a trap that was set up for her. I’m interested to see where her story goes.

The gender politics of the different societies are also handled with a light but incisive touch. The historical analogues to each fantastical culture provide backdrops for commentary, certainly, but Range of Ghosts never stops at criticism of the flaws of a society. It always offers insight into the women and men living within it, and why they do the things they do; even the Rahazeen sect, the murder-cult, are given levels of depth during Edene’s captivity. The actual Uthman empire does not appear in full in Range of Ghosts, as the group’s travels have just taken them to the edges, but I look forward to the same nuanced exploration of an Islam-inspired culture—and this version is already quite interesting, as the Scholar-God is considered female.

The ways of the steppes, where women are not considered as part of dynastic succession—the moons in the sky are only sons and grandsons—and are frequently married by abduction and rape, are balanced by the freedom of those same women to choose their bed-partners as they like and to be respected as leaders and advisers. The ugly and the beautiful are both explored. That complexity, an unwillingness to be utopian and an unwillingness to be unrelentingly grim, is a breath of fresh air in the epic genre. Real lives are complex, real cultures are complex; it is worth attempting to explore that in fiction—and Bear does so in Range of Ghosts.

Additionally, the women in this book tend to be women with solid bodies: big hips, bellies, and muscles—and none of that is remarkable to any other character. It’s just the way things are, and it is positive, and it is beautiful. Temur’s feverish perception of Samarkar as Mother Night when he first meets her is particularly striking: “He knew her by her eyes, by the muscle in her arms, by the breadth of her shoulders, and by the bounty of her belly and her breasts. He knew her because she lifted him up and set him on Bansh’s back when he could no longer cling there himself” (143). Women as savior figures, as wizards, as kings—in the last section of Range of Ghosts, we encounter a woman-king—and as queens, as in need of the occasional rescue but able to rescue themselves, as realized human beings. That’s just the cherry on top of an all-around great book, with a gripping plot and fabulous intrigues.

I also realized, upon reading this novel, how much I’ve missed series that aren’t afraid to have separate books that are obviously all one giant story—where the first book is the first third of the story, and proudly so. Books written to be read as stand-alones while also part of a series are just fine, but they seem to have become the norm, whereas books that are not isolated but contiguous have become rarer. This is not to say that Range of Ghosts can’t stand alone—it does end with a satisfying climactic scene, and contains a great set of narratives—but it is clearly and wonderfully the beginning of a large story with one central plot arching over the projected three books. What resolutions are offered here are in service of opening up a larger field of events; the resolutions themselves are satisfying, but moreso is the lingering curiosity and sense of wonder that prompts me to check the calendar for when I can read the next volume.

Range of Ghosts is a strong beginning to a big story about fascinating, flawed, believable people. I closed the novel with a desperate curiosity about what comes next, for the characters and their world; I found the book itself to be a well-written, well-constructed read with precise prose dedicated to balancing fifty things at once in most scenes. All around a great piece from Elizabeth Bear, and I recommend it for readers who want stunning, crunchy world-building, complex conflicts, and women characters who aren’t just strong but are also powerful. It’s the “big, fat fantasy with maps” you’ve been waiting for, if you’re much like me.

This article was originally published March 27, 2012

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.